COMPILED BY GLOBAL CIVILIANS FOR PEACE IN LIBYA

When analysing the standard of living in Libya it is important to put the achievements into context. During the 1950’s under the leadership of King Idris, Libya was amongst the poorest nations in the world with some of the lowest living standards. From the early 1980’s until 2003 Libya were placed under heavy sanctions by the US and UN which had the result of strangling Libya’s growing economy leading to an inevitable smothering of development projects and social welfare schemes. Despite this The Libyan Arab Jamahiriya achieved the highest living standard in Africa. Libya has also invested heavily in African development initiatives. The funding of infrastructure projects as well as African political and financial institutions was aimed at developing Africa independently and combating the economic exploitation of African resources and labour by outside powers.

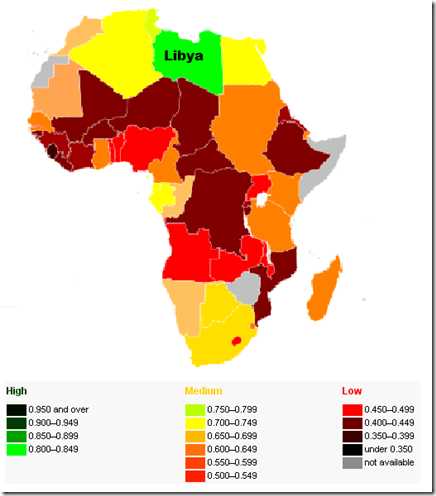

Human Development Index

The Human Development Index (HDI) is a composite statistic used to rank countries by level of “human development” and separate “very high human development”, “high human development”, “medium human development”, and “low human development” countries. The Human Development Index (HDI) is a comparative measure of life expectancy, literacy, education and standards of living for countries worldwide. It is a standard means of measuring well-being, especially child welfare. It is used to distinguish whether the country is a developed, a developing or an under-developed country, and also to measure the impact of economic policies on quality of life.

2010 HDI

Human Development Index: Trends 2005 – 2010

Each year since 1990 the Human Development Report has published the Human Development Index (HDI) which was introduced as an alternative to conventional measures of national development, such as level of income and the rate of economic growth. The HDI represents a push for a broader definition of well-being and provides a composite measure of three basic dimensions of human development: health, education and income. Libyan Arab Jamahiriya’s HDI is 0.760, which gives the country a rank of 64 out of 187 countries with comparable data. The HDI of Arab States as a region increased from 0.444 in 1980 to 0.641 today, placing Libyan Arab Jamahiriya above the regional average. Learn more

Public Health Care

Public Health Care in Libya prior to NATO’s “Humanitarian Intervention” was the best in Africa. “Health care is [was] available to all citizens free of charge by the public sector. The country boasts the highest literacy and educational enrolment rates in North Africa. The Government is [was] substantially increasing the development budget for health services…. (WHO Libya Country Brief )

Confirmed by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), undernourishment was less than 5 %, with a daily per capita calorie intake of 3144 calories. (FAO caloric intake figures indicate availability rather than consumption).

The Libyan Arab Jamahiriya provided to its citizens what is denied to many Americans: Free public health care, free education, as confirmed by WHO and UNESCO data.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO): Life expectancy at birth was 72.3 years (2009), among the highest in the developing World.

Under 5 mortality rate per 1000 live births declined from 71 in 1991 to 14 in 2009

(http://www.who.int/countryfocus/cooperation_strategy/ccsbrief_lby_en.pdf)

Libyan Arab Jamahiriya General information

2009

Source: UNESCO. Libya Country Profile

Libyan Arab Jamahiriya (2009)

Total life expectancy at birth (years) 72.3

Male life expectancy at birth (years) 70.2

Female life expectancy at birth (years) 74.9

Newborns with low birth weight (%) 4.0

Children underweight (%) 4.8

Perinatal mortality rate per 1000 total births 19

Neonatal mortality rate 11.0

Infant mortality rate (per 1000 live births) 14.0

Under five mortality rate (per 1000 live births) 20.1

Maternal mortality ratio (per 10000 live births) 23

Source WHO http://www.emro.who.int/emrinfo/index.aspx?Ctry=liy

Education

The adult literacy rate was of the order of 89%, (2009), (94% for males and 83% for females). 99.9% of youth are literate (UNESCO 2009 figures, See UNESCO, Libya Country Report)

Gross primary school enrolment ratio was 97% for boys and 97% for girls (2009) .

(see UNESCO tables at http://stats.uis.unesco.org/unesco/TableViewer/document.aspx?ReportId=121&IF_Language=eng&BR_Country=4340&BR_Region=40525

The pupil teacher ratio in Libya’s primary schools was of the order of 17 (1983 UNESCO data), 74% of school children graduating from primary school were enrolled in secondary school (1983 UNESCO data).

Based on more recent date, which confirms a marked increase in school enrolment, the Gross Enrolment Ratio (GER) in secondary schools was of the order of 108% in 2002. The GER is the number of pupils enrolled in a given level of education regardless of age expressed as a percentage of the population in the theoretical age group for that level of education.

For tertiary enrolment (postsecondary, college and university), the Gross Enrolment Ratio (GER) was of the order of 54% in 2002 (52 for males, 57 for females).

(For further details see http://stats.uis.unesco.org/unesco/TableViewer/document.aspx?ReportId=121&IF_Language=eng&BR_Country=4340&BR_Region=40525

Women’s Rights

With regard to Women’s Rights, World Bank data point to significant achievements.

“In a relative short period of time, Libya achieved universal access for primary education, with 98% gross enrollment for secondary, and 46% for tertiary education. In the past decade, girls’ enrollment increased by 12% in all levels of education. In secondary and tertiary education, girls outnumbered boys by 10%.” (World Bank Libya Country Brief, emphasis added)

Price Controls over Essential Food Staples

In most developing countries, essential food prices have skyrocketed, as a result of market deregulation, the lifting of price controls and the eliminaiton of subsidies, under “free market” advice from the World Bank and the IMF.

In recent years, essential food and fuel prices have spiralled as a result of speculative trade on the major commodity exchanges.

Libya was one of the few countries in the developing World which maintained a system of price controls over essential food staples.

World Bank President Robert Zoellick acknowledged in an April 2011 statement that the price of essential food staples had increased by 36 percent in the course of the last year. See Robert Zoellick, World Bank

The Libyan Arab Jamahiriya had established a system of price controls over essential food staples, which was maintained until the onset of the NATO led war.

While rising food prices in neighbouring Tunisia and Egypt spearheaded social unrest and political dissent, the system of food subsidies in Libya was maintained.

Prof. Michel Chossudovsky http://www.globalresearch.ca/index.php?context=va&aid=26686

United Nations Development Programme (UNDP)

2005-2015

The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) is the United Nations‘ global development network. It advocates for change and connects countries to knowledge, experience and resources to help people build a better life. UNDP operates in 166 countries, working with nations on their own solutions to global and national development challenges. As they develop local capacity, they draw on the people of UNDP and its wide range of partners.

The Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) are eight international development goals that all 193 United Nations member states and at least 23 international organizations have agreed to achieve by the year 2015. They include eradicating extreme poverty, reducing child mortality rates, fighting disease epidemics such as AIDS, and developing a global partnership for development

Libya’s GDP per capita income as of 2005 was estimated at US$ 10,335, well above the mean rates for medium human development countries. Government subsidies in health, agriculture, and food imports, alongside domestic income, education, and health indicators significantly support the achievement of this goal. As such, MDG Goal 1 is likely to be achieved within the 2015 timeframe.

Illiteracy rates in Libya have fallen from 61 per cent in 1971 to 14 per cent in 2001. As of 2005, the combined gross enrolment ratio for primary education stood at 95.9, thus ensuring that Libya is likely to achieve MDG Goal 2 within the 2015 timeframe. (Human Development Report 2007/2008)

The Libyan legislature has strived to ensure that women in Libyan society are granted their full rights before the law, ensuring compatibility and consistency of Libyan legislative acts with those of the provisions of internationally recognized conventions. In addition, significant progress in gender equality has been most evident in education and health. While there is still much to be done in ensuring gender parity in political and economic representation, Libya is likely to achieve MDG Goal 3 within the 2015 timeframe. (Human Development Report 2007/2008)

In Libya, infant mortality rates have decreased from 105 per 1000 live births in 1970, to 18 in 2005. Mortality rates amongst children under five have seen a similar shift, with 24 per 1000 live births in 2005. Libya is therefore considered to be on track, and very likely to achieve MDG Goal 3 within the 2015 timeframe. (Human Development Report 2007/2008)

In 2005, maternal mortality in Libya was recorded at 97 per 100,000 live births. While this figure is above the average for high human development countries, Libya is working towards achieving MDG Goal 5, with 94% of births attended by skilled health personnel. With increased attention to public health delivery, Libya is likely to be achieve goal 5 within the 2015 time frame.

While the human resources for health planning, production and management pose a considerable challenge in Libya, the gradual reintegration of the country into the international economy is leading to better availability of healthcare. The government provides free healthcare to all citizens and has achieved high coverage in most basic health areas. Furthermore, the government is substantially increasing the development budget for health services, and has already prepared clear-cut and comprehensive strategies for HIV/AIDS and TB. Consequently, Libya is likely to be achieve goal 6 within the 2015 time frame.(Human Development Report 2007/2008)

Limited investment is being made in renewable energy sources, while NGO’s and CSO’s are pursuing eco-tourism ventures and nature conservation activities. However, there is still much to be done in terms of establishing recycling plans, promoting responsible power management and increasing education on the issue. Nevertheless, Libya is likely to be achieved within the 2015 time frame.(Human Development Report 2007/2008).

Through the establishment of CENSAD (The Community of Sahel-Saharan States) and continued support to the african Union, Libya has made significant contribution towards partnership for development in Africa.

source: http://www.undp-libya.org/index.php

Poverty Line

’Poverty” defined as an economic condition of lacking both money and basic necessities needed to successfully live, such as food, water, education, healthcare, and shelter. There are many working definitions of “poverty,” with considerable debate on how to best define the term. Income security, economic stability and the predictability of one’s continued means to meet basic needs all serve as absolute indicators of poverty. Poverty may therefore also be defined as the economic condition of lacking predictable and stable means of meeting basic life needs.

The poverty threshold, or poverty line, is the minimum level of income deemed necessary to achieve an adequate standard of living in a given country. In practice, like the definition of poverty, the official or common understanding of the poverty line is significantly higher in developed countries than in developing countries.

Population Living Below National Poverty Line based on CIA World Factbook (2010)

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Percent_poverty_world_map.png

https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/

World Health Organisation – Health and Development in Libya (2007)

Health status has improved: The Government provides free health care to all citizens. The country

has achieved high coverage in most basic health areas. The mortality rate for children aged less than 5 years

fell from 160 per 1000 live births in 1970 to 20 in 2000. In 1999, 97% of one-year-old children were

vaccinated against tuberculosis and 92% against measles.

Disease control: The priority areas are: noncommunicable diseases, HIV/AIDS prevention and control,

tuberculosis (TB) and disease surveillance. A strategic plan for 2005–2009 for HIV/AIDS includes theintroduction of a harm reduction programme, voluntary testing and counselling. Cardiovascular diseases,hypertension, diabetes and cancer account for significant mortality and morbidity. The risk factorscontributing to noncommunicable diseases also include emerging obesity and high level of smoking. Roadtraffic accidents (RTA) result in 4–5 deaths per day and are a major burden of disease.

Health services: The General People’s Committee (GPC) through the Central Health Body isresponsible for direction and performance of health services and health status. The actual execution is the mandate of the shabiat. Almost all levels of health services (promotive, preventive, curative and rehabilitative) are decentralized, except Tripoli Medical Centre and Tajoura Cardiac Hospital, which are centrally run. A growing private health sector is emerging. The Government encourages the expansion of private clinics and hospitals. The family physician practices and health insurance are being introduced. The country enjoys a very high rate of primary health care.

Health information system: The objective of national health information system strategy supports and enhances the CCS and all its strategic elements, including disease surveillance, burden of disease studies,health promotion, monitoring of national health related Millennium Development Goals (MDGs).

Water supply and sanitation: The Great Man-made River (GMR) project is transporting fresh water from underground aquifers in the south-east to supply major urban areas in the north. Also 11 new water desalination plants are being built. The environmental problems include over-exploitation of groundwater resources, pollution and poor waste management. A national approach is needed to link the environmental health activities, including food safety to related disease control programmes.

Currently, the Libyan Arab Jamahiriya receives no external funds as development aid from any source of any kind. The contribution of UN agencies other than WHO to health development has been relatively scarce. UNDP is actively working in the health sector through two UN thematic groups. The HIV/AIDS group has been functional since 2003. The UNDP to conduct rapid assessment of drug abuse and the drug abuse thematic group has just been formed. Technical cooperation existed with Italy.

Library of Congress – Country Studies

Data as of 1987

Medical Care

The number of physicians and surgeons in practice increased fivefold between 1965 and 1974, and large increases were registered in the number of dentists, medical, and paramedical personnel. Further expansion and improvement followed over the next decade in response to large budgetary outlays, as the revolutionary regime continued to use its oil income to improve the health and welfare of all Libyans. The number of doctors and dentists increased from 783 in 1970 to 5,450 in 1985, producing in the case of doctors a ratio of 1 per 673 citizens. These doctors were attached to a comprehensive network of health care facilities that dispensed free medical care. The number of hospital beds increased from 7,500 in 1970 to almost 20,000 by 1985, an improvement from 3.5 beds to 5.3 beds per 1,000 citizens. During the same years, substantial increases were also registered in the number of clinics and health care centers.

A large proportion of medical and paramedical personnel were foreigners brought in under contract from other Arab countries and from Eastern Europe. The major efforts to “Libyanize” health care professionals, however, were beginning to show results in the mid1980s . Libyan sources claimed that approximately 33 percent of all doctors were nationals in 1985, as compared with only about 6 percent a decade earlier. In the field of nursing staff and technicians, the situation was considerably better–about 80 percent were Libyan. Schools of nursing had been in existence since the early 1960s, and the faculties of medicine in the universities at Tripoli and Benghazi included specialized institutes for nurses and technicians. The first medical school was not established until 1970, and there was no school of dentistry until 1974. By 1978 a total of nearly 500 students was enrolled in medical studies at schools in Benghazi and Tripoli, and the dental school in Benghazi had graduated its first class of 23 students. In addition, some students were pursuing graduate medical studies abroad, but in the immediate future Libya was expected to continue to rely heavily on expatriate medical personnel.

Among the major health hazards endemic in the country in the 1970s were typhoid and paratyphoid, infectious hepatitis, leishmaniasis, rabies, meningitis, schistosomiasis, and venereal diseases. Also reported as having high incidence were various childhood diseases, such as whooping cough, mumps, measles, and chicken pox. Cholera occurred intermittently and, although malaria was regarded as having been eliminated in the 1960s, malaria suppressants were often recommended for use in desert oasis areas.

By the early 1980s, it was claimed that most or all of these diseases were under control. A high rate of trachoma formerly left 10 percent or more of the population blinded or with critically impaired vision, but by the late 1970s the disease appeared to have been brought under control. The incidence of new cases of tuberculosis was reduced by nearly half between 1969 and 1976, and twenty-two new centers for tuberculosis care were constructed between 1970 and 1985. By the early 1980s, two rehabilitation centers for the handicapped had been built, one each in Benghazi and Tripoli. These offered both medical and job-training services and complemented the range of health care services available in the country.

The streets of Tripoli and Benghazi were kept scrupulously clean, and drinking water in these cities was of good quality. The government had made significant efforts to provide safe water. In summing up accomplishments since 1970, officials listed almost 1,500 wells drilled and more than 900 reservoirs in service in 1985, in addition to 9,000 kilometers of potable water networks and 44 desalination plants. Sewage disposal had also received considerable attention, twenty-eight treatment plants having been built.

Housing

Housing was one of the major concerns of the revolutionary government from the beginning, and the provision of adequate housing for all Libyans by the 1980s has remained a top priority. The former regime had undertaken to build 100,000 units to relieve a critical housing shortage, but this project had proved an expensive fiasco and was abandoned after 1969. A survey at the time of the revolution found that 150,000 families lacked decent shelter, the actual housing shortfall being placed at upward of 180,000 dwellings.

Both the public and private sectors were involved in housing construction during the 1970s. Private investment and contracting accounted for a large portion of all construction until new property ownership laws went into effect in 1978 that limited each family to only one dwelling. Despite the decline of privately financed undertakings, the housing sector constituted one of the most notable of the revolution’s achievements. By the late 1970s, the hovels and tenements surrounding Benghazi and Tripoli had begun to give way to modern apartment blocks with electricity and running water that stretched ever farther into what had once been groves and fields. These high-rise apartments became characteristic of the skylines of contemporary Benghazi, Tripoli, and other urban areas.

Between 1970 and 1986, the government invested some LD2.8 million (for value of the Libyan dinar (LD–see Glossary) in housing, which made possible the construction of 277,500 housing units, according to official sources. To reach these targets, the regime drew not only upon Libyan resources but also enlisted firms from France, the Federal Republic of Germany (West Germany), Spain, Italy, Turkey, the Republic of Korea (South Korea), and Cuba. Since 1984, budget allocations for housing have fallen in keeping with a general decline in government spending. Many housing contracts have been suspended or canceled as a result, causing financial difficulties for foreign firms. A shortfall in new construction also raised the prospect of overcrowding and the creation of new shantytowns as the country’s burgeoning population threatened to overwhelm the supply of housing.

Source: http://lcweb2.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/r?frd/cstdy:@field(DOCID+ly0069)

Nations Encyclopedia

Libya: Poverty and Wealth

The living standards of Libyans have improved significantly since the 1970s, ranking the country among the highest in Africa. Urbanization, developmental projects, and high oil revenues have enabled the Libyan government to elevate its people’s living standards. The social and economic status of women and children has particularly improved. Various subsidized or free services (health, education, housing, and basic foodstuffs) have ensured basic necessities. The low percentage of people without access to safe water (3 percent), health services (0 percent) and sanitation (2 percent), and a relatively high life expectancy (70.2 years) in 1998 indicate the improved living standards. Adequate health care and subsidized foodstuffs have sharply reduced infant mortality, from 105 per 1,000 live births in 1970 to 20 per 1,000 live births in 1998. The government also subsidizes education, which is compulsory and free between the ages of 6 and 15. The expansion of educational facilities has elevated the literacy rate (78.1 in 1998). There are universities in Tripoli, Benghazi, Marsa el-Brega, Misurata, Sebha, and Tobruq. Despite its successes, the educational system has failed to train adequate numbers of professionals, resulting in Libya’s dependency on foreign teachers, doctors, and scientists.

Many direct and indirect subsidies and free services have helped raise the economic status of low-income families, a policy which has prevented extreme poverty. As part of its socialist model of economic development,

the Libyan government has weakened the private sector and confined it to mainly small-scale businesses. While this policy has damaged the Libyan economy significantly, it has also prevented the accumulation of wealth by a small percentage of the population.

Read more: Libya Poverty and wealth, Information about Poverty and wealth in Libya http://www.nationsencyclopedia.com/economies/Africa/Libya-POVERTY-AND-WEALTH.html#ixzz1dFBakVah

(Extract)

21 February 2011

During Muammar Gaddafi’s 42-year rule, Libya has made great strides socially and economically thanks to its vast oil income, but tribes and clans continue to be part of the demographic landscape.

Women in Libya are free to work and to dress as they like, subject to family constraints. Life expectancy is in the seventies. And per capita income – while not as high as could be expected given Libya’s oil wealth and relatively small population of 6.5m – is estimated at $12,000 (£9,000), according to the World Bank.

Illiteracy has been almost wiped out, as has homelessness – a chronic problem in the pre-Gaddafi era, where corrugated iron shacks dotted many urban centres around the country.

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/mobile/world-middle-east-12528996

The Great Man Made River

18 March 2006

Libyans like to call it “the eighth wonder of the world”.

The description might be flattering, but the Great Man-Made River Project has the potential to transform Libyan life in all sorts of ways.

Libya is a desert country, and finding fresh water has always been a problem.

Following the Great Al-Fatah Revolution in 1969, when an army coup led by Muammar Al Qadhafi deposed King Idris, industrialisation put even more strain on water supplies.

Coastal aquifers became contaminated with sea water, to such an extent that the water in Benghazi (Libya’s second city) was undrinkable.

Finding a supply of fresh, clean water became a government priority. Oil exploration in the 1950s had revealed vast aquifers beneath Libya’s southern desert.

According to radiocarbon analysis, some of the water in the aquifers was 40,000 years old. Libyans call it “fossil water”.

![]() The quality of life is better now, and it’s impacting on the whole country

The quality of life is better now, and it’s impacting on the whole country ![]()

Adam Kuwairi, GMRA

After weighing up the relative costs of desalination or transporting water from Europe, Libyan economists decided that the cheapest option was to construct a network of pipelines to transport water from the desert to the coastal cities, where most Libyans live.

Proud nation

In August 1984, Muammar Al Qadhafi laid the foundation stone for the pipe production plant at Brega. The Great Man-Made River Project had begun.

Click here to see a map of the pipeline network

Libya had oil money to pay for the project, but it did not have the technical or engineering expertise for such a massive undertaking.

Foreign companies from South Korea, Turkey, Germany, Japan, the Philippines and the UK were invited to help.

It is impossible not to be impressed with the scale of the project

In September 1993, Phase I water from eastern well-fields at Sarir and Tazerbo reached Benghazi. Three years later, Phase II, bringing water to Tripoli from western well-fields at Jebel Hassouna, was completed.

Phase III which links the first two Phases is still under construction.

Adam Kuwairi, a senior figure in the Great Man-Made River Authority (GMRA), vividly remembers the impact the fresh water had on him and his family.

“The water changed lives. For the first time in our history, there was water in the tap for washing, shaving and showering,” he told the BBC World Service’s Discovery programme.

“The quality of life is better now, and it’s impacting on the whole country.”

To get an idea of the scale of the Great Man-Made River Project, you have to visit some of the sites.

The Grand Omar Mukhtar will be Libya’s largest man-made reservoir

Libya is opening up, but it’s still hard for foreign journalists to get visas. We had to wait almost six months for ours; but once we arrived in Libya, Libyans were eager to tell us about the project.

They took us to see a reservoir under construction at Suluq. When it’s finished, the Grand Omar Mukhtar will be Libya’s largest man-made reservoir.

Standing on the floor of such a huge, empty space is an awesome experience. Concrete walls rise steeply to the sky; tarring machines descend on wires to lay a waterproof coating over the concrete.

Further west along the coast is the Pre-Stressed Concrete Cylinder Pipe factory at Brega. This is where they make the 4m-diameter pipes that transport water from the desert to the coast.

![]() Libyans are gaining experience and know-how, and now more than 70% of the manufacturing is done by Libyans

Libyans are gaining experience and know-how, and now more than 70% of the manufacturing is done by Libyans ![]()

Ali Ibrahim, Brega pipe factory

It’s a modern, well-equipped factory, built specially for the Great Man-Made River Project. So far, the factory has made more than half a million pipes.

The pipes are designed to last 50 years, and each pipe has a unique identification mark, so if anything goes wrong, engineers can quickly establish when the pipe was made.

The engineer in charge of the Brega pipe factory is Ali Ibrahim. He is proud that Libyans are now running the factory: “At first, we had to rely on foreign-owned companies to do the work.

“But now it’s government policy to involve Libyans in the project. Libyans are gaining experience and know-how, and now more than 70% of the manufacturing is done by Libyans. With time, we hope we can decrease the foreign percentage from 30% to 10%.”

Opening markets

With fossil water available in most of Libya’s coastal cities, the government is now beginning to use its water for agriculture.

Over the country as a whole, 130,000 hectares of land will be irrigated for new farms. Some land will be given to small farmers who will grow produce for the domestic market. Large farms, run at first with foreign help, will concentrate on the crops that Libya currently has to import: wheat, oats, corn and barley.

Libya also hopes to make inroads into European and Middle-Eastern markets. An organic grape farm has been set up near Benghazi. Because the soil is so fertile, agronomists hope to grow two cereal crops a year.

Water is seen as key to the country’s future prosperity

It is hard to fault the Libyans on their commitment. They estimate that when the Great Man-Made River is completed, they will have spent almost $20bn. So far, that money has bought 5,000km of pipeline that can transport 6.5 million cubic metres of water a day from over 1,000 desert wells.

As a result, Libya is now a world leader in hydrological engineering, and it wants to export its expertise to other African and Middle-Eastern countries facing the same problems with their water.

Through its agriculture, Libya hopes to gain a foothold in Europe’s consumer market.

But the Great Man-Made River Project is much more than an extraordinary piece of engineering.

Adam Kuwairi argues that the success of the Great Man-Made River Project has increased Libya’s standing in the world: “It’s another addition to our independence; it gives us the confidence to survive.”

Of course, there are questions. No-one is sure how long the water will last. And until the farms are working, it’s impossible to say whether they will be able to deliver the quantity and quality of produce for which the planners are hoping.

But the combination of water and oil has given Libya a sound economic platform. Ideally placed as the “Gateway to Africa”, Libya is in a good position to play an increasingly influential role in the global economy.

http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/sci/tech/4814988.stm

The Great Man-Made River

The Great Man-Made River is a network of pipes that supplies water from the Sahara Desert in Libya, from the Nubian Sandstone Aquifer System fossil aquifer. Some sources cite it as the largest engineering project ever undertaken.

The Guinness World Records 2008 book has acknowledged this as the world’s largest irrigation project.

According to its website, it is the largest underground network of pipes and aqueducts in the world. It consists of more than 1300 wells, most more than 500 m deep, and supplies 6,500,000 m³ of freshwater per day to the cities of Tripoli, Benghazi, Sirt and elsewhere. Muammar al-Gaddafi has described it as the “Eighth Wonder of the World.